Some people regard Raffaello Sanzio (or Raphael as he’s known in English) as the greatest painter of the Renaissance. Others know him as the badass Mutant Ninja Turtle with the red bandana wielding a three-pronged Sai blade. Whichever Raphael you recognise, you’re among friends here at Carpe Diem.

You'll find no judgment here. We’re a broad church.

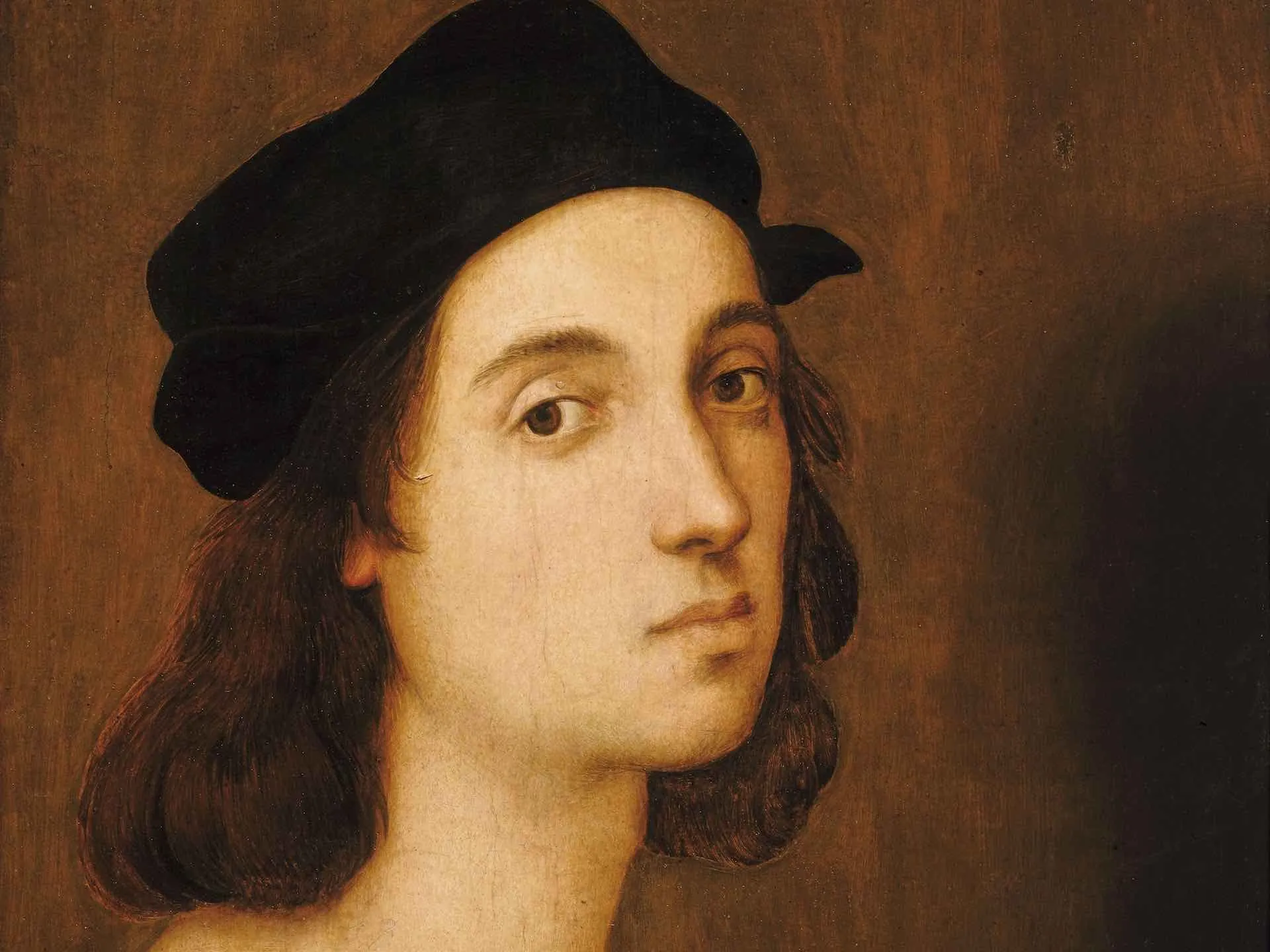

Raphael was born in 1483 in Urbino, a small artistic centre in central Italy. His father Giovanni was a notable artist and court painter to the duke. Raphael grew up in a painter’s workshop, mixing paints, using a stylus and paintbrush from a young age. But his childhood bliss was shattered by the untimely death of his parents.

By just 11, Raphael was an orphan, fending for himself and helping manage his father’s workshop. He completed his first commissioned work (the Baronci Altarpiece) before the age of 20, paving the way for regular commissions. During his short career, Raphael was extremely productive in creating altarpieces, portraits, and Madonnas in Urbino, a chapel in Siena and then he moved to Florence.

All the Great Masters of the day were all there: Leonardo, Botticelli, Pinturicchio, Rosselli and Perugino, his mentor. These impressive names had painted the Sistine Chapel in the 1480s, the often-overlooked band below the ceiling with the lives of Moses and Jesus. He would also come into contact with the work of another talented genius Michelangelo who was 8 years older.

Unlike his contemporary Ninja Turtles, Raphael worked continuously producing whatever the client wanted in fabulous style. Leonardo was famous for leaving commissions unfinished and preferred engineering and his inventions. Michelangelo was a cantankerous character, demanding and difficult to work with. Raphael on the other hand knew how to behave at court, was charming, easy-going and amiable to everyone he met.

Raphael was 25 when he rode into Rome through the Porta Flaminia in 1508. He had been summoned by Bramante (lead architect at the Vatican) to paint a fresco in the private apartment of Pope Julius II. The pope was so impressed he fired the other painters (including Perugino, Raphael’s teacher) and gave him all the rooms to decorate; these are known as the Raphael Rooms today.

When Julius died, the new Pope Leo X took a liking to Raphael and commissioned a set of designs for tapestries to hang in the Sistine Chapel, a commission of huge importance. Later he made him the architect of St Peter’s Basilica and gave him the unenviable task of deciding the fate of Roman antiquities that were uncovered.

Raphael worked continuously throughout his twelve years in Rome, not just at the Vatican, also for notable elites including the richest man in Rome and the pope’s banker, Agostino Chigi.

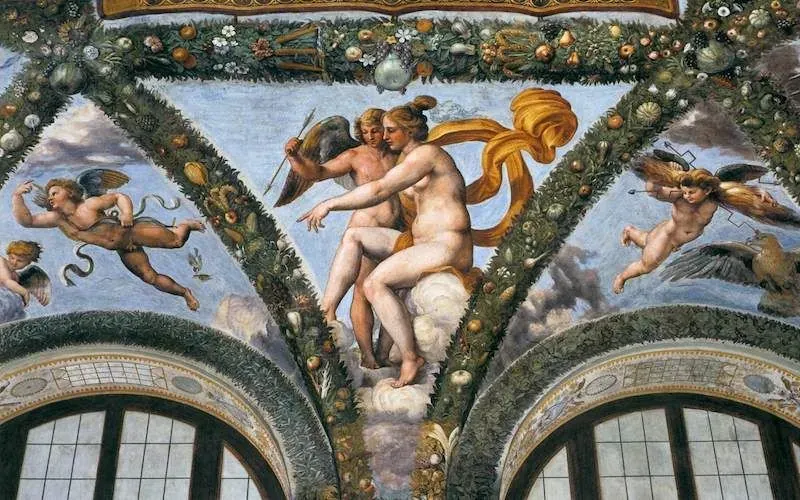

For Chigi he would create the most titillating images of his career. At the Villa Farnesina, often neglected by tourists is the loggia dedicated to the story of Cupid and Psyche. Grand, mythological frescoes dripping with sensuality and seduction, seamlessly placed in a garden setting. Renaissance soft porn at its finest.

Raphael’s fresco in Villa Farnesina’s Loggia of Cupid and Psyche. Wikipedia Commons.jpeg

The biographer Vasari claims Raphael was so excited by his own images that he kept running off to see his lover; so, Agostino installed her in the villa at great expense to allow Raphael to make love and work without jeopardising the project. A more sombre project was the Chigi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo, Agostino’s tomb.

Much has been made of the apparent rivalry between the two artists, yet they were poles apart. Michelangelo was a sculptor; He believed that painting was for girls, and was merely a glorified form of colouring in while he unleashed the form of man from marble. Yet Pope Julius II cancelled a sculptural work from him and forced Michelangelo to paint an enormous ceiling at the advice of Bramante. Michelangelo would complain for the rest of his life it was a setup and that Raphael was involved.

Michelangelo certainly envied Raphael’s popularity at court and the numerous commissions he received. When Leo X became pope after Julius II, he chose Raphael as lead artist over Michelangelo who had grown up at his court. He was no doubt incensed that the younger man was made architect of the Vatican. But he would have the last laugh, even claiming in later life that he had taught Raphael everything he knew!

Michelangelo was always complaining. He presented himself as a downtrodden, tortured soul and lived like a beggar, barely washing and leaving his boots on for months at a time. He was well-paid for his commissions, yet he lived like a pauper, proudly declaring he ate only stale bread. In reality, he was a complicated character. A devout catholic struggling with his religion and repressed homosexuality; he was worlds apart from the young, attractive and affable Raphael.

We know nothing of Raphael’s opinion. A famous story tells how Bramante allowed him a sneak-peek of the partially completed Sistine fresco. He was so awestruck by Michelangelo’s work that he added a figure to his own ‘School of Athens’, using the same brushwork as on the ceiling. A moody Heraclitus with the face and boots of Michelangelo. In the fresco's original designs, the figure is suspiciously absent, but we can only wonder if this was deference to the artist, or mocking him.

Raphael’s School of Athens in the Vatican Museums

Although she died when he was only eight years old, Raphael’s mother was clearly of great importance to him. Described as a gentle and affectionate woman, many believe their loving relationship can be seen in Raphael’s numerous Madonna’s. Unlike earlier depictions, he showed a closeness and sensitivity of a loving mother and her child, not Mary and Christ.

Above all, Raphael was able to capture women in all their grace and loveliness. Michelangelo’s women are like men with a breast popped on the chest. When we compare the work of the two great masters, it is clear that unlike Michelangelo, Raphael was certainly familiar with female flesh and had seen many a naked woman!

In Rome, he lived like a prince at court surrounded by the most beautiful women in town. He is often portrayed as a Casanova figure, bedding whomever he wanted; yet the true love of his life was one of his models and rumour had it, a famous courtesan. Margherita Luti was the daughter of a baker (Fornaio) in Trastevere, her nickname ‘La Fornarina’ comes from her father’s job, although some suggest it was her working name and can be translated ‘little hottie’.

“La Fornarina” by Raffaello Sanzio

She appears as a model in several of his paintings, but we also have an intensely personal portrait of her which can be seen at Palazzo Barberini in Rome. She is topless in the picture, unheard of in a portrait at that time and has an intense, loving gaze as she looks at the viewer (or the painter). On her ring finger we can see a small ring and a blue ribbon on her arm, curiously signed by Raphael; almost as if the painter is claiming ownership.

He was officially engaged to the niece of an important cardinal, Maria Bibiena in 1514, but she died the same year as Raphael still a maid. Many believe he had already married in secret to Margherita. La Fornarina was painted a few years before his death and one wonders whether he painted it for her or himself. Regardless, their love affair has become timeless.

A life cut tragically short, Raphael died, as he was born on Good Friday. The official record would ascribe his death to a fever, but Vasari tells us the fever was brought on by a day-long bout of love-making with his mistress.

‘He wouldn’t tell the doctors what had brought on the fever so they gave him the wrong treatment and his body was too weak to survive’.

Whether it was medical malpractice or too much sex, we will never know but many believe this was a kind way of saying he had caught syphilis during his adventures with the fleshpots of Rome.

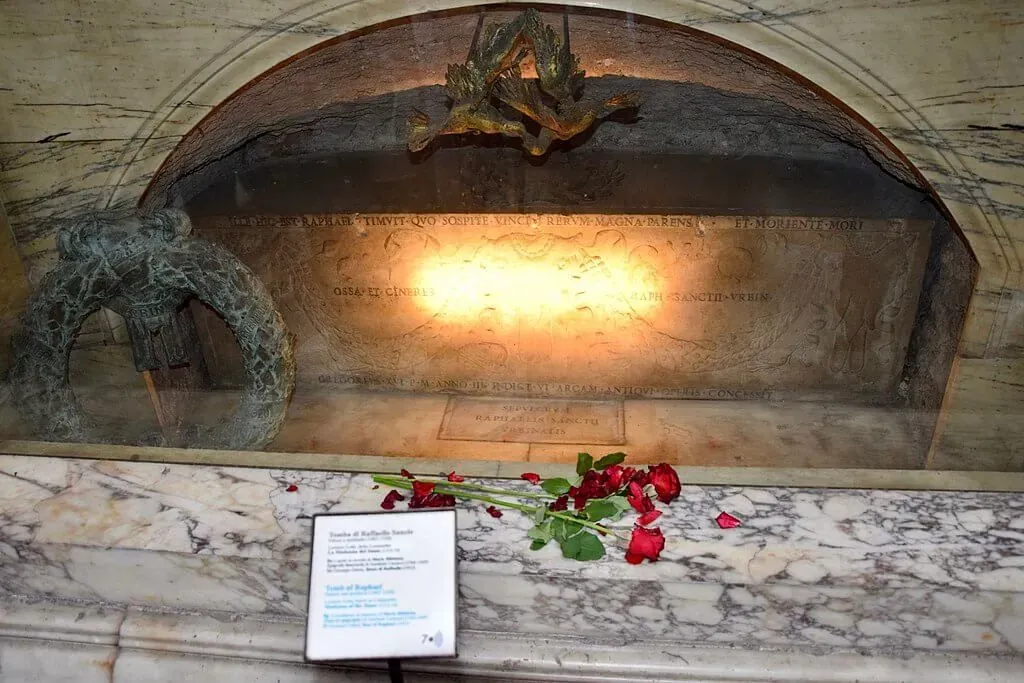

At his own request, Raphael was buried with great pomp and ceremony in the Pantheon. His friend Lorenzetto sculpted a Madonna for his tomb and three Italian regions mourned his passing. He lies in an ancient Roman sarcophagus with the inscription:

Here lies Raphael. Feared by Nature while he lived, when he died, Nature feared that she herself would die, without him.

Raphael’s tomb in Rome’s Pantheon

Despite his short life, Raphael left an enormous corpus of work that traces the development of his style. He could copy and absorb the work of his mentors and contemporaries like no other artist and using their skills create something entirely his own. When he died, he controlled the largest apprentice workshops of any of the Great Masters. Many went on to become great artists in their own right.

No headings found in content.