The Romans are often celebrated for their ingenious public engineering works: the graceful arches of their aqueducts, the grandeur of their bathhouses, and the grim efficiency of their sewers. The remains of these monuments are the focus of many Rome tours today, and are proof – we like to think – that the Romans were at the cutting edge. But when we compare their sanitary standards to ours, Rome’s glossy marble starts to crack.

Many of the innovations we associate with hygiene in ancient Rome did not always improve sanitation. In some cases, they made things far, far worse.

In this article we’ll be exploring just how dirty the Romans were, looking at public health, disease, toilets, sewers, and the sensory world of everyday life. Brace yourself: ancient Rome was a city of astonishing achievement, but also of pervasive stench, constant noise, and a startling intimacy with filth. And some of the following content will shock you.

Ancient Rome never had any clear Roman public health policy. What existed was a patchwork of reactive measures, cobbled together only when disaster struck. One early law, most likely arising from an outbreak of dysentery or cholera, forbade burials and cremations within the city walls. Yet citizens long persisted in ignoring it, dumping the corpses of slaves or unwanted infants throughout the city’s streets and inside its sewers — more on which later.

Burial Monuments Lining the Appian Way in Rome

Only in the 3rd century BC, after a ferocious plague struck the city, did the Romans consecrate Tiber Island as a healing sanctuary with its own Asklepion (temple of healing). The island’s founding myth speaks to how deeply pestilence shaped Roman consciousness. When plague ravaged the city in 293 BC, the Senate consulted the Sibylline Oracles and dispatched envoys to Epidaurus, the god’s Greek sanctuary. They returned with a sacred snake, Asclepius incarnate, which leapt (somehow) from their ship and swam ashore onto the island.

%20in%20Rome)

Rome's Tiber Island. A sanctuary of healing since the 3rd century BC

This myth reads nicely, but it reflects a grimmer reality. The Romans had recognised the need to isolate their infected, and a small island in the middle of the River Tiber was ideal.

Roman cities teemed with microorganisms that thrived in waste. Cholera and other waterborne diseases were widespread wherever sewage mixed with drinking supplies, whether at the fountains, in the baths, or in the fast-flowing River Tiber. Malaria also flourished in what was a paradise for mosquitoes: standing water in basins, gutters, fountains, and, ironically, bathtubs.

Scientists have recently discovered a parasite that afflicted people throughout the Roman Empire. Although not strictly a disease, it’s still pretty disgusting. The Romans loved garum, a fermented fish sauce that provided the Roman diet with salt in the form of a dark-colored, strong-tasting, and rather smelly liquid — and they exported this condiment to every province. The problem is that this raw fish sauce spreads eggs that then grows into tapeworms of up to 20 to 25 feet long, coiling around the intestines of those unfortunate enough to consume it.

Faecal matter also formed part of the urban landscape, and came not just from animals but from humans too. Sh*t filled the streets of every Roman city, as attested by numerous written sources and examples of graffiti begging passers-by not to do it outside their house. Laws had to be written to punish citizens who dumped dung or filth into the water supply, and that such laws were necessary tells you everything.

But step outside the city walls and the situation was not much improved.

The Romans reused human excrement in ways that would alarm any public health officer in the industrialised world: as a cheap and plentiful form of fertiliser. The agricultural writer Varro describes slave privies built directly above manure pits. A later writer, Columella, recommends sludge from the sewers as an excellent soil supplement. He tells us that human manure is “the very finest,” though best reserved for soils so poor they require extra nourishment.

So how did Roman farmers get their faeces? Well, some poor souls had to fetch it.

Cesspit-emptying became a regular urban job. In Herculaneum, one graffito records an 11-as payment (a pitiful amount) “for removal of ordure.” A sh*t job, quite literally — but essential nonetheless. In Rome, a night cart would pass by and collect refuse from toilets not connected to the sewers.

Learn more stomach-churning facts on our Rome Tipsy Tour!

When you got laid low by disease, to whom could you go? Until the time of the Roman Empire, Rome had no public physicians. By the late 1st century, the medical profession had diversified to include medici publici (public doctors), surgeons, oculists, physicians for gladiators, physicians for slaves, and the imperial court’s own high-earning healers — as well as magicians and quacks who would promise to cure you of your malady for a fraction of the price.

Doctors enjoyed enviable perks: exemption from taxes, immunity from billeting soldiers, relief from prison, and premium seats at the games. Julius Caesar even granted citizenship to every physician practicing in Rome. But their skill varied dramatically. The Lex Aquilia offered damages for medical negligence, and jurists like Ulpian record punishments for lethal potions sold as “aphrodisiacs.”

Still, quack doctors were everywhere. One, Diaulus, got suitably skewered by the 1st-century poet Martial:

“Diaulus, lately a doctor, is now an undertaker: what he does as an undertaker, he used to do also as a doctor.”

From the reign of Antoninus Pius (138–161 AD), physicians were required to present accreditation. Yet free medical care for the poor wasn’t mandated until late in Roman history in 386 AD: a remarkably late development for a civilisation often credited with inventing the Western city. Hospitals for soldiers and slaves existed from the 1st century AD, but hospitals for civilians didn’t appear until Christianity pushed charitable care forward. And none of this stopped catastrophe: the Plague of Justinian (6th century AD) ravaged the empire for more than half a century, helping finish off the Western Empire.

The impact of all of this was predictably grim. While some wealthy Romans might live into their 60s or even 70s, life expectancy at birth in Rome averaged just 25 years.

Ancient Rome had an impressive variety of toilets: public latrines (foricae), private household toilets, cesspit systems, and sewer-connected facilities. Yet none of these worked quite as hygienically as modern visitors might assume.

In Rome, only the houses of the elite connected directly to the main sewer, the Cloaca Maxima. Everyone else relied on cesspits. Most toilets were on the ground floor, but not all of them. In some insulae — the multi-storey apartment blocks where most Romans lived — upper-floor toilets emptied into terracotta downpipes. Over time, these cracked or loosened, sending their contents cascading down the building’s exterior or into the rooms of tenants downstairs.

In Pompeii, nearly every house had a toilet, usually positioned next to or inside the kitchen. Only one has been found to have had a water flush. The rest emptied into cesspits cut into porous volcanic rock.

Household cooks often worked beside built-in latrines placed there out of convenience. Waste liquids, peelings, and scraps went straight down the hole. But the risks were enormous. Cross-contamination would have been constant. The smell would have been overwhelming. Insects (cockroaches especially) would have thrived. For all the talk of poisoning in ancient Rome, we might want to take a closer look at the kitchen.

Many Romans preferred cesspit toilets to sewer-connected ones. Why? Because sewers regularly flooded, and lacking traps, allowed anything—rats, snakes, even sea creatures—to come crawling back up. Aelian, writing in the 3rd century AD, recounts a tale of an octopus that swam from the sea, through a sewer, and into a merchant’s home in Pozzuoli to devour his pickled fish. Terrifying? Absolutely. Implausible? Not necessarily.

Public latrines were social spaces, but they could also be hazardous. With no U-bend in the sewers or trap system beneath the seats, methane and hydrogen sulphide from the sewers gradually built up. As a result, explosions occurred — occasionally lethal for the poor souls tasked with cleaning the sewers. Some Romans blamed malevolent spirits dwelling in the pipes.

We know that there were 144 public latrines in Rome by the 4th century AD. Pompeii was even more latrine-rich, with toilets found everywhere from bars to tiny shops. Most lacked running water. Most lacked washing facilities. All were covered in graffiti:

“On April 19th, I made bread.”

(Almost certainly a euphemism. Found in a latrine.)

“We have wet the bed… there was no chamber pot.”

(Left by frustrated travellers in an inn.)

“Apollinaris, doctor to the Emperor Titus, had a good crap here.”

(Given that Titus died of a curable disease aged 41, this may have been his doctor’s life’s work.)

A more sanitary question comes to mind. After scribbling something on the wall, how did the Romans wipe themselves? The famous sponge-on-a-stick (tersorium) is often mentioned in texts, but archaeologists still debate whether it was used on the body or simply for cleaning the latrine seat. Either way, the communal aspect is clear—and unsettling.

To save going downstairs in the middle of the night and making the dangerous journey to the public latrines, most Romans would have relieved themselves in chamber pots and then disposed of them in the morning. They were pretty inventive as to what form these chamber pots could take. Martial talks about a drunkard called Panaretus relieving himself in a wine jar and filling it back up to the brim. (Rather grimly, he proceeds to take a swig).

But where would you have emptied it? Good citizens might have carried a brimming chamber pot down to the public latrines, but the less scrupulous would have probably poured the contents out the window or directly onto the streets below. Ulpian (9.3.1) discusses the laws and punishments surrounding chucking stuff out of one’s window and onto public thoroughfares. For example, the fine for killing a freeperson is 50 gold coins, and should it be the son of the household who throws something out the window and kills someone, it is he who is liable and not the head of the household (paterfamilias). He also provides evidence that someone died from having a chamber pot landing on their head.

If ancient Rome had a smell, a good part of it would be down to the fullers.

Fulleries were the ancient equivalent of dry cleaners, and one of their key ingredients was urine. Urine is rich in ammonia, and therefore perfect for degreasing and whitening clothes. To keep the supply to the fulleries flowing, terracotta jars were set out in streets and alleyways so passersby could make their contribution.

There was, however, a problem.

The terracotta jars for collecting urine were often unglazed and porous. They cracked easily in the heat, leaked constantly, and had an unfortunate habit of spilling their contents onto the street. Imagine a summer afternoon in Rome: already hot, already crowded, and now decorated with the occasional splash of warmed human urine.

Sometimes, the Romans did better. At Ostia Antica, the so-called Baths of Mithras were directly connected to a nearby fullery via a lead pipe, allowing used bathwater to be channelled straight into the fullers’ vats. Efficient, yes. Hygienic, no.

Urine was valuable enough that Emperor Vespasian famously taxed it. When his son Titus reproached him for the indignity of taxing something so disgusting, Vespasian held a coin under his nose and asked whether it smelled. When Titus said no, his father delivered the punchline that’s echoed down the centuries: pecunia non olet—“money doesn’t stink.”

It’s a shame the same couldn’t be said for Rome’s streets.

The Romans were immensely proud of their sewers. Strabo, writing around the turn of the millennium, marvelled at the scale of the underground world:

“The sewers, covered with a vault of tightly fitted stones, have room in some places for hay wagons to drive through them… almost every house has water tanks, and service pipes, and plentiful streams of water.”

For Roman writers, the sewers ranked alongside the roads and aqueducts as proof of Roman greatness. Pliny the Elder called them a work “more stupendous than any,” noting that mountains had to be pierced and that, like Babylon, ships could effectively pass beneath the city. Dionysius of Halicarnassus put it succinctly: the aqueducts, the paved roads, and the drains were the three supreme achievements of the empire.

Pliny also preserves a darker side to this triumph. The sewers, he says, were begun under King Tarquinius Priscus, who conscripted Rome’s lower classes to dig them. The work was so brutal and so prolonged that many labourers chose suicide rather than continue.

Tarquinius responded with a characteristically Roman mixture of pragmatism and cruelty: he ordered that anyone who killed themselves be crucified after death and left on display as carrion. The logic was macabre but effective. Romans might not fear suffering after death, but they did fear public shame. Suicides dropped, and the project continued.

We’re told that the sewers were made large enough to admit a wagon loaded with hay, and that seven artificial rivers were forced to flow beneath the city, carrying away waste and stormwater alike. Swollen by rain and by the overflow of fountains and basins, these subterranean torrents reverberated along their channels and swept the filth of a million-person city towards the Tiber.

That is a lot of filth. Rome may have produced 40–50,000 kilograms of human waste every day, much of it eventually funnelled into or through the sewer system.

The Cloaca Maxima today. Image credit: Encylopedia Britannica

Dirty or not, the water running through the sewers was still “living” in Roman eyes—and therefore sacred. It’s no accident that the Cloaca Maxima, Rome’s first great sewer, had its own protective deity: Venus Cloacina, “Venus of the Sewers”, who watched over the city’s drains. Even excrement, in Rome, had its goddess.

Of course, once you build a giant U-shaped sewer system, you have to maintain it. Roman sewers tended to silt up, block, and backflow. Someone had to go in and fix that.

A letter from the emperor Trajan (98–117 AD) to Pliny the Younger sheds some light on who drew the short straw. Condemned men, Trajan notes, were often assigned to work in the public baths, clean out the sewers, and repair roads and streets.

Learn all about Trajan's Column on our Rome Walking Tour!

Sewer cleaning was penal or slave labour. Those condemned to do it worked in claustrophobic, poorly ventilated tunnels, exposed to hydrogen sulphide, methane, stagnant water, and whatever else a city of one million people could flush, tip, or throw away. Death by suffocation or poisoning was a constant risk.

There was also an engineering incentive to keep the sewers flowing. Jurist Ulpian warns that neglected drains could undermine mud foundations and cause buildings to collapse. So if the smell and the gas didn’t convince the city to send someone down, the threat of sudden structural failure might.

According to Agrippa’s census of 33 BC, Rome already boasted 170 public and private baths. By the 4th century AD, that number had swollen to nearly 1,000. Admission was cheap—a quadrans, the smallest coin in circulation—so almost everyone could afford to go. We don’t know how strictly they were closed at night, and it’s not unreasonable to imagine people dozing in the warm, steamy rooms after hours.

Reconstruction of the Baths of Caracalla

A typical visit involved moving between different temperature rooms: a cold plunge, a hot chamber, and the more popular warm room—the tepidarium—where bathers lingered, chatted, and relaxed.

Think of it like a large, warm swimming pool with no chlorine and no filtration system. Now picture hundreds of bodies, day after day, sliding in and out of that same water. The Romans certainly urinated in the baths; even with attendants glaring at them, some people always do. Add to that sweat, oils, skin flakes, and whatever pathogens they brought in, and you have a near-perfect breeding ground for diseases like dysentery and cholera.

One mercy: children were generally not allowed in the baths. Adults went daily; kids were expected to make do at home with a bucket of water drawn from the local fountain. It’s a small concession to hygiene, but a concession nonetheless.

Bath-goers brought clean clothes, towels, oils and ointments, and a strigil—a curved metal scraper used to remove a mixture of oil, sweat, and dirt from the skin. Contrary to expectations, strigil-cleaning is actually quite effective. You emerge feeling genuinely scrubbed.

The water, however, remained dubious. Baths were rarely drained and refilled; instead, they were periodically flooded to push off the worst of the scum. Over time, a cloudy film of oil, grime, and organic matter would build up on the surface. Several Roman writers couldn’t resist pointing out the irony: citizens seeking health in a place where they effectively marinated in each other’s body residue. As part of Roman bathing’ etiquette, the sick usually bathed in the afternoons to avoid healthy bathers. However, like public toilets and the streets, there was no daily cleaning routine for keeping the baths themselves clean, so illness was often passed to healthy bathers who visited the next morning.

Baths weren’t just about washing. They were gyms, social clubs, medical clinics, and political meeting points rolled into one. One thing they were not, in the modern sense, was clean.

A popular epigram, found on the tombstone of Tiberius Claudius Secundus and repeated across the empire, captures the Roman attitude perfectly:

Balnea, vina, Venus corrumpunt corpora nostra,

sed vitam faciunt balnea, vina, Venus.

“Baths, wine, and sex ruin our bodies,

but baths, wine, and sex make life worth living.”

Another epitaph from Ostia has a man named Primus boast that he lived on Lucrine oysters and Falernian wine, and that baths, wine, and love aged with him through the years. If he achieved that, he says, may the earth lie light on him. No regrets. Just oysters.

Not everyone saw the baths as grim reapers in disguise. The Christian writer Minucius Felix praises the marine baths of Ostia as a soothing remedy, taken while the law courts were on holiday. Archaeology backs up the idea of baths as health centres: statues of healing deities, including Asclepius, have been found in Ostian bath complexes.

Health hazard or health cure? In true Roman fashion, the answer seems to be “both.”

All of this bathing, flushing, and sewer-scouring depended on the real heroes of Roman sanitation: the aqueducts.

The Pont du Gard in France, one of the most impressive surviving Roman aqueducts

By the early Empire, nine major aqueducts supplied Rome (more still were added later). Seven of their lines still stride through what is now the Parco degli Acquedotti, including the later Aqua Felice. Before the first aqueduct was built in 312 BC, the Romans relied on the Tiber, on rainwater collected in cisterns, and on the odd spring. That means there was a span of a couple of centuries where Rome had a sewer system funnelling filth away — but no truly reliable way of bringing fresh, clean water in.

The aqueducts changed that dramatically. Ancient engineers boasted that they carried more water than all the hand-built monuments of Greece combined. They weren’t exaggerating. At their peak, Rome’s aqueducts supplied over 992,000 cubic metres of water a day: that’s about 992 million litres, or roughly 262 million gallons.

Tom Ripley walks along the Claudian Aqueduct at the end of an eventful night. Image credit: Netflix

Break it down per person, and you’re looking at around 992 litres (263 gallons) per head, per day—more than double what most of us use now (about 100 gallons), and we’re the ones with flush toilets and hot showers. Most of Rome’s water went not into cleaning waste away, but into fountains, baths, ornamental displays, and industrial uses like fulleries.

As Dionysius of Halicarnassus put it, the aqueducts, the roads, and the drains were the empire’s crowning achievements. They were spectacular. They were effective. And still, Rome stank.

If you’d walked Rome’s streets in antiquity, you’d have encountered a sensory overload that puts modern traffic and pollution into perspective. The roads were littered with human and animal waste. Corpses of slaves and exposed, unwanted infants could be left out in some districts. There were no municipal street-cleaning crews in the modern sense. The responsibility for urban upkeep lay with the aediles, magistrates with limited resources and competing priorities.

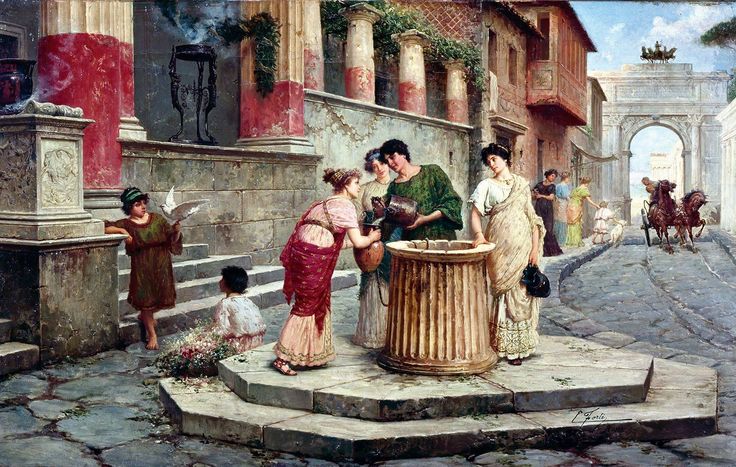

A Pompeii Street by Ettore Forti. Life was not as sanitary as this idealised painting suggests.

One famous anecdote has the emperor Caligula, furious at Vespasian’s neglect of his street-cleaning duties as aedile, ordering soldiers to shovel mud into the folds of his purple-bordered toga. It was a humiliating reminder that Rome’s filth was everyone’s problem—especially the man whose job it was to hide it.

Excess water didn’t always stay underground. When sewers backed up or overflowed, fouled water bubbled out into the streets. Refuse was picked over by dogs, pigs, and carrion birds. The air would have buzzed with flies.

In Pompeii, the famous raised stepping stones that still dot the streets were not whimsical design features. They were practical survival tools. They allowed pedestrians to cross the road without stepping directly into whatever mixture of mud, dung, urine, and kitchen waste was flowing between the ruts left by cart wheels. It was, quite literally, a city built with the expectation that the road would often be running with filth.

Raised stepping stones in Pompeii prevented people from treading in sewage and garbage

In many ways, ancient Rome wasn’t uniquely disgusting. It was simply ahead of the curve in being large and crowded. Its sanitation problems were the same ones that plagued every major European city right up to the 19th century.

Conditions in Rome would, in fact, have looked depressingly familiar to residents of industrial London before its modern sewer system was built. It wasn’t until reformers like Edwin Chadwick and his famous Sanitary Report in the mid-1800s that governments seriously invested in large-scale public health infrastructure.

Modern Romans, incidentally, often find us unhygienic. Many can’t imagine a bathroom without a bidet, and they’re mildly horrified that so much of the Anglophone world makes do without one. Standards change. The debates continue.

If you’d like to experience ancient Rome in person (minus the smell), Carpe Diem Tours would love to show you around. Our Rome walking tours, Colosseum tours, and famously indulgent Tipsy Tour fully immerse you in the ancient city: from the bustle of the Roman Forum to the underbelly of the Suburra — ancient Rome's red light district.

Want to visit an ancient Roman city, immaculately preserved in place with your expert private guide? Check out our Private Ostia Antica Tour.

No headings found in content.

Join us on a journey through Roman history on our immersive Rome by Night Walking Tour. Your expert guide will share the city’s secrets, history, and fascinating tales—from antiquity through to the modern day, and at a pace to suit you.

Our tour starts in Rome’s most picturesque square, Piazza Navona, where the ancient Romans used to watch athletic contests (agones). Today’s piazza sits above the ancient stadium and boasts Gian Lorenzo Bernini‘s stunning Fountain of the Four Rivers as its centrepiece.

A five-minute walk from Piazza Navona takes us to the world-famous Pantheon. Constructed more than two-thousand years ago by the eccentric emperor Hadrian, the Pantheon was consecrated as a monument to all the pagan gods (pan theos, in Greek meaning all the gods). This second-century temple is one of the best-preserved monuments in the Roman Empire and its unreinforced concrete dome still perplexes architects.

Our next stop is the iconic Trevi Fountain. Immortalised by Anita Ekberg wading through its water in Federico Fellini’s iconic film La Dolce Vita, the Trevi Fountain one of the most romantic spots in the Eternal City. Snap your photos of the monument in the moonlight, listen to your guide decipher its symbols, and toss a coin over your shoulder to guarantee your return to Rome.

We emerge from Rome’s winding backstreets onto Piazza Venezia. Stretching from the foot of the Capitoline Hill, against the backdrop of the Altar of the Fatherland, Piazza Venezia is Rome’s most recognisable square, and a repository of history involving figures from Napoleon to Mussolini.

Your guide will lead you down the Via dei Fori Imperiali, the boulevard that cuts through ancient Rome, past Trajan’s Column and alongside the forums of Trajan, Augustus and Nerva. Your guide will feed your curiosity and nourish you with knowledge about ancient Rome and its empire as you make your way towards the most famous monument of all: the Colosseum.

The Colosseum is one of the most awe-inspiring attractions that has survived from antiquity. As a colossal feat of architecture and engineering, its form has been replicated throughout the ages, manifested in stadiums and sports venues around the world. But while its form is familiar to us, the spectacles it accommodated are entirely alien, and remind us of the violent nature of Roman culture.

Group sizes are 15 people maximum.

Book your spot now to avoid missing out!

Channel your inner-Maximus as you step out onto the Colosseum Arena floor and access this recently reopened area of the world-famous amphitheatre. Then, explore the rest of the heart of ancient Rome, with a friendly, expert guide and a small group of like-minded travellers!

Unlike regular tours of the Colosseum, our Colosseum Arena Tour gets you straight inside the ancient amphitheatre and out onto the arena floor through the Gladiator’s Gate. This is the route the gladiators themselves took almost 2,000 years ago. Imagine the moment they left the gates, and were greeted by the cheers and jeers of 50,000 bloodthirsty spectators.

Your expert guide will transport you back in time to the height of the Roman Empire when the Colosseum was constructed. These were times when Rome was ruled by all-powerful emperors (sometimes wise, sometimes wacky), the city was flooded with exotic riches from around the world, and the Colosseum acted as the city’s main stage for showing off the animals and people that Rome had conquered and captured.

After a short 30-minute break, we’ll head off on the next part of the tour…

Next, we’ll climb the Palatine Hill, where the ancient city was founded. The Palatine Hill is a real archaeological wonder, home to settlements from the Iron Age to the 16th century. Gaze upon such sites as the Hut of Romulus, Rome’s legendary founder, and the Imperial Palace, where the emperors in their family engaged in ruling, politicking, and scheming. Get your camera at the ready because you really can’t beat these views!

The final destination on our Colosseum Arena Tour is the Roman Forum. As the beating heart of ancient Rome, the Roman Forum was once a bustling hub of markets, law courts, temples, and more. It was here that Julius Caesar was cremated, where victorious triumphs paraded with the spoils of Roman conquests, here where two disgraced emperors were murdered in 69 AD, and here where Cicero delivered the speeches that shaped Western culture for centuries.

When our tour is over, feel free to stay and explore the Roman Forum at your own pace.

Book the complete ancient Roman experience today with our Colosseum Arena Tour!

Want a more personalised experience? Upgrade to a Semi-Private Arena Tour with a maximum of 12 people per group, or treat yourself to a Private Arena Tour and spend it with the ones you care about most.

Feed your curiosity as you please your palate on this indulgent Rome Food Tour! There's a reason our tour is multi-award-winning, and it's because we give you an all-access pass to savouring the Eternal City, stress-free. With everything pre-arranged, you’ll bypass the crowds as you taste your way through Rome; no queues, no guesswork—just authentic Roman cuisine. This fun (and filling) food tour gives you and a group of fellow foodies a taste of the city's culinary treasures, from local delicatessens and pizzerias to traditional trattorias and restaurants, you'll try all the authentic spots that the locals keep to themselves but your guide will reveal to you.

Our award-winning Rome food tour takes place in Trastevere, Rome's most traditional medieval neighbourhood. While the area is renowned for its buzzing nightlife and world-class cuisine, just like the rest of Rome, this neighbourhood also has its fair share of tourist traps. That's why we have teamed up with the places that keep to traditions and serve food for locals.

Because holidays are too short to eat badly, right?

This food tour in Rome will treat your tastebuds to at least 10 different tastings (vegetarian options available!) perfectly paired with a selection of local wines or non-alcoholic beverages for sober travellers. Try crispy Roman-style pizza by the slice, savoury supplì, and the best gelato in the city. Experience is more than just simply trying local cuisine, it's a glimpse inside the Roman kitchen—discovering the delicacies, the diet and the cultural dos and don’ts.

While you taste your way through the capital on this food tour; Rome will fully open up as you’ll also discover the process, meet the makers, and truly understand why Italian cuisine is considered the best in the world. So book your spot on our Rome Food Tour today and get ready for a true taste of the capital!

Please note: the places that we visit and the food that we try depend on the season.

Looking for a more intimate local experience with no strangers? We now offer an exclusive semi-private Rome food tour for groups of 6 or fewer.

This is a sustainable tour, meaning part of its profits go towards reforestation and other sustainable projects. We also ask all of our guests to bring a reusable water bottle to refill at one of the water fountains along our route to stay hydrated and help us reduce waste.

**Unfortunately, we can’t accommodate a gluten-free or vegan diet, but we hope to be able to in the future. While we can cater to vegetarians, we ask that you let us know about dietary requirements in advance so we can best suit your needs.**

Explore the wonders of the Eternal City on our best of Rome walking tour. As you get your bearings around Rome’s cobbled historic centre, your expert storyteller will bring Rome’s most must-see sites to life, including the Pantheon, Trevi Fountain, and Piazza Navona. Take photos, make memories, and most importantly, get the most out of your time in the Italian capital!

Your private guide will share the city’s secrets and narrate its story in a way that will make you feel like you’ve stepped back in time – from explaining how the stunningly intricate churches and palaces were erected, to how the grand fountains were used to channel water throughout the city.

We will start at Trajan’s Column, which portrays the bloody victory of the emperor during the Dacian wars in Eastern Europe. We’ll then head to the Piazza Venezia, the crossroads between the ancient city and the modern capital and one of the most scenic squares in Italy!

After taking a moment to marvel at the imposing Altar of the Fatherland, we’ll make our way to the iconic Trevi Fountain. Toss a coin into the fountain, spend a moment soaking in its sounds and scenery (metaphorically, not literally!), and uncover the fascinating stories behind the fountain’s statues and symbols.

After discovering the incredible frescoes within the church of Sant Ignazio, we’ll make our way to the Pantheon where the spectacle of the 2000-year-old dome will blow you away. Marvel at one of the best-preserved buildings of the ancient world, hear the story behind the man who built it, and discover the shocking architectural secret behind how the dome is (or isn’t) supported!

Your private walking tour of Rome finishes at Piazza Navona. The square is situated near some of Rome’s best and most vibrant bars and restaurants and your guide will be happy to recommend where to go.

This tour is suitable for people of all ages and fitness levels. You can expect this memorable experience to last about two hours, which leaves you with more than enough time to explore the city beyond.

Discover the flavours of Rome on our Spritz and Spaghetti Class. Our centrally located kitchen is where you’ll learn everything you need to mix traditional Italian cocktails, and perfect the art of making fresh pasta. This is the only cooking class of its kind in Rome – a perfect blend of food, friends, and tipsy fun. So come join us and see what all the fuss is about!

Our team will welcome you and your small, intimate group with a mixology demo making Italy’s best-loved drink: Aperol Spritz. You’ll then get started on your hands-on pasta-making lesson led by a fun-loving, fluent professional chef before making a Hugo Spritz.

Your professional chef will guide you every step of the way – from kneading the dough to cutting the pasta. You’ll also be making a creamy carbonara sauce to coat your fresh pasta (vegetarians can try out another Roman classic of cacio e pepe). Travelling is all about meeting new people. At the end of this cooking class, you’ll dine on what you’ve made with a glass of Limoncello Spritz to wash it all down.

Book now and start making memories.

Although our Rome Golf Cart tour follows a tried-and-tested itinerary, upon special request it can be 100% customisable—so you can hone in on the attractions that interest you most.

Forget the fatigue of traipsing around the Eternal City. This tour saves you time and energy as you see all the capital’s must-see sites in half the time. Jump aboard your horseless chariot and let us chauffeur you around Rome in comfort and convenience. Enjoy exclusive access to traffic-limited areas, and enjoy hopping on and off your golf cart straight at the foot of your attraction of choice.

Visit the stunning Trevi Fountain, immortalized in Fellini’s classic film La Dolce Vita, and throw a coin over your shoulder to ensure your return to Rome! Admire the tumbling terraces and balustrades of the famous Spanish Steps, and discover what exactly it is that makes the monument Spanish!

Gaze up in awe at the Pantheon, Rome’s best-preserved ancient temple, and learn the fascinating history of how it was founded and how it has fared. Drive to the foot of Piazza Navona, Italy’s most stunning square, which was built above an ancient structure your guide will bring to life.

Your Rome Golf Cart tour takes you up the Aventine Hill, where Romulus’ brother Remus tried—but failed—to found his city. Pass by the Orange Garden, stopping off to enjoy its views, and check out the famous Keyhole View over Saint Peter’s Basilica and the Territory of the Order of the Knights of Malta.

Stop off at the famous Mouth of Truth situated right by the River Tiber in the area where Rome was founded. This stunning stretch of road around the most ancient part of the Eternal City also takes us past the Theatre of Marcellus (a building started by Julius Caesar and finished by the emperor Augustus) and the impressive Capitoline Hill.

You can choose where your tour finishes: in Rome’s centre, at your hotel, or wherever you want to explore next! If you’d like to visit the Colosseum, Castel Sant’Angelo or the Vatican on your Golf Cart Tour of Rome, we can also arrange for this, depending the time and location of your departure or finish point.

For all special requests, please contact us directly.

Learn to cook like an Italian in this small group pasta & tiramisù cooking class that gives you mastery over the country’s best-loved classics. Over the course of three fun-filled hours, you’ll enjoy the expert guidance of our fluent professional chef and get hands on recreating real Roman recipes, culminating in a well-deserved dinner and dessert.

Situated in our centrally situated air-conditioned cooking school, your interactive class will give you the true sense of an Italian nonna’s loving kitchen. Led by an enthusiastic and knowledgeable English-speaking chef, our cooking masterclass is perfect for kids and adults, beginners and experts.

Savoiardi (ladyfingers) are gently dipped in rich coffee before being layered with dollops of delicately mixed eggs and panna (cream). Finished off with a sprinkle of cocoa, these delicious desserts are set aside to rest in time for an after-dinner energy boost. In fact, the espresso within a tiramisù is what gives it a name that translates literally as “pick me up”!

Rolling up our sleeves, here is where we channel our inner nonna. Mixing, kneading, rolling, and shaping our fresh pasta from scratch will work up a sweat but result in elegant end products. We will then combine these carefully crafted creations with the flavours of the season and locality; be it twangy cacio e pepe or creamy carbonara.

How else to conclude your cooking class than by fully indulging in your culinary creations! Celebrate your accomplishment with family-friendly company, a gorgeous setting, and a glass of local wine or prosecco.

Whether returning a culinary maestro or a self-proclaimed novice, you’ll be sure to take the memories home with you and ruling your dinner parties back home!

With your Fun and Witty English Mother-Tongue guide, we will take you off the beaten path and bring ancient Roman society to life, telling the stories behind the art and architecture. Showing you the hidden masterpieces that you absolutely have to see before you leave Rome.

We will visit the Bones Capuchin Crypts. Six Crypts decorated with the Bones of almost 4000 monks. Art and symbols of Christianity made from Human Bones. You will see works by Caravaggio and Learn the intricacies of religious burial rights as we try to grasp that universal question.

Next we will walk past the Colosseum and the Ludas Magnus where the Gladiators trained before going 4 levels underground to the Basilica of S. Clemente – a 12th century Basilica built on top of a 4th century Basilica, built on top of a 2nd century Temple of Mythros, On top of a 1st century Roman Apartment block.

Starting with the 12th century Basilica we will learn about the relics of the 4th Pope. Continuing down to the 4th century Basilica where you will discover the early formation of the Christian Church and admire the frescoes and symbols within. See the earliest written vernacular Italian in the world. Moving down to a 2nd century Mithra temple and seeing a 1st century Apartment Block with its fountain that has been running for over 2000 years.

Rome may well be the world’s most beautiful city, but after dark a more sinister side emerges. The ghosts of popes, emperors, and artists lurk on every corner, their lives claimed by tragedy and conspiracy across more than 2,000 years of history. Our Rome Ghost Tour is not for the faint hearted — you’ll hear the ghastly tales of beheadings and murder that are sure to keep you up late at night.

Your Rome Ghost Tour starts at Campo de’ Fiori, a central square, where you’ll be treated to the tale of Giordano Bruno, one of Rome’s greatest minds who got on the wrong side of the church. After learning about his grisly end, you’ll begin to explore the city. Venture through medieval backstreets; visit an ancient church adorned with skulls; and step inside the home to a mysterious order of monks. Discover the childhood home of one of Rome’s most infamous executioners; see the site of one of Rome’s most infamous prisons; and pass by a poisonous perfumery where cosmetics killed.

Your tour ends at the imposing Castel Sant’Angelo, where your guide will reveal the horror of Rome’s most disturbing executions. If you’re (un)lucky, you might even encounter a ghost or two.

No matter what, you’ll never see Rome the same way again.

This isn’t your average elementary school pizza party; this is Rome, and we’re turning up the heat! Just ten minutes from the Colosseum, our high-energy cooking class is where pizzas fly and glasses are raised high.

In this dough-lightful evening experience, you’ll toss, top, and toast your way through a night of pizza-making, drink-sipping, and full-on Roman revelry. Ready to make your very own pizza? You’ll get a slice of pizza history from Rome and beyond, and a charismatic local chef will show you how to work the dough like a pro.

Roll, knead, and spread the dough before topping it off with everything your heart desires, except pineapple of course, we've got to stick to the rules. Then, as the dough rises, so does the mood because you'll get a crash course in Italian mixology. Sip on traditional Italian cocktails like Aperol and Hugo Spritz and socialise with your fellow chefs while your pizza bakes to Roman perfection.

Then, when everything is ready, it’s time to eat! You’ll dine like the Italians over a homemade pizza while continuing to sip on a Limoncello Spritz until your heart's content. You know the saying, when life gives you lemons, we turn it into a toast.

Whether you’re coming with friends, your amore, or are ready to make new pizza-loving pals, this isn’t just dinner, it’s a hands-on, wine-filled, flour-dusted party you’ll never forget.

So come hungry, bring your appetite for fun, and let’s raise a glass (and a pizza peel) to the tastiest night of your Roman holiday!

One of the best ways to meet people in a new city is to grab a drink together, and few city serve up more iconic drinks than Rome. Whether you’re travelling solo or with a group, for a long vacation or a short city break – our Rome Tipsy Tour is for you!

This unique nightlife experience combines all our favourite elements of travel: discovering new places, being immersed in different cultures, meeting fun people, and trying out a range of delicious drinks! It’s not a run-of-the-mill bar crawl. It’s a sociable tour that gives you a real taste of with Rome’s sights, stories, and signature drinks in a friendly, relaxed atmosphere with fun, local hosts. We also welcome sober travellers who want to join for a social experience but who want to forgo a hangover, so we’ll have non-alcoholic options available as well!

You’ll meet your guide and group at Piazza Madonna dei Monti, where we’ll break the ice with a warm Italian welcome – aka, a refreshing glass of local wine. After saying cheers—salute—we’ll head into Monti, an uber-trendy district filled with quirky bars and cobblestoned streets, and plenty to unpack. In ancient Rome, Monti was known as a suburra – the red-light district of Rome where prostitutes plied their trade and gangsters once roamed. As we wander through the cobblestone streets your guide will tell you scandalous stories of sex and bloodshed that you won’t hear on your typical walking tour.

After so much scandal, you’ll surely need a drink. So at our first stop on the Rome Tipsy Tour you’ll get an extra stiff one. The spotlight will be on Carpano Classico a venerable vermouth with a curious story! Unravel the history of the man who made it – Antonio Benedetto Carpano – back in 1786 whilst sharing some sips with your newfound friends.

We’ll keep the night going with some more saucy stories before trying a classic Italian Spritz. Indulge in the bitter flavours of Aperol or Campari Spritz while enjoying dolce far niente, the sweetness of doing nothing—apart from getting tipsy of course!

Our final stop is Rome’s most iconic road, the Via dei Fori Imperiali, leading down to the Colosseum. The views of the ancient city are best enjoyed after dark with an ice-cold Limoncello – trust us. Sip away as your guide tells shocking stories of the power-hungry Roman emperors who once ruled the known world.

At 11 p.m., the Tipsy Tour officially ends, but the night out begins! We will continue drinking with our new friends at some of Rome’s most popular bars!

Don’t miss out on this once-in-a-lifetime experience. We promise to make your night in Rome one you’ll never forget! Skip a boring walking tour, and come get tipsy with us.

Book your spot now!

After this class, the Eternal City is sure to steal a pizza your heart. This midday culinary experience is perfect for families, kids, and anyone who believes lunch should come with a side of laughter (and dessert). You’ll be mixing, kneading, laughing, and layering your way through two of Italy’s most iconic dishes: pizza and tiramisù.

We’ll meet in our centrally located kitchen, just a stone’s throw away from the Colosseum. Here you’ll roll up your sleeves and get ready for a delicious adventure from start to finish. A local chef will teach you about the different styles of pizza before you craft your own from scratch. Make and knead the dough, then get creative with toppings before firing it up to golden, cheesy perfection.

But wait—there’s s’more! After the pizza party, it’s time to sweeten things up with a tiramisù-making session. It’s creamy, dreamy, and sure to tirami-woo the crowd.

After everything is cooled and baked, you’ll sit down and enjoy your culinary masterpieces with your fellow chefs. The best part? Parents can also enjoy a glass of local wine or prosecco. It’s more than a meal, it’s a memory in the making, sprinkled with a touch of cocoa powder.

What are you waiting for? Grab your spot, bring your appetite, and get ready for a slice of fun that the whole famiglia will love.

Experience Ostia Antica with the exclusive attention of a licensed expert guide and archaeologist, whose deep knowledge and personalised approach turn the ancient port city into a vivid, immersive world. Because this is a private tour, your guide tailors the experience entirely to you—focusing on the parts of Ostia that most spark your curiosity, whether that's daily Roman life, religion, engineering, trade, or the city’s remarkably intact architecture.

As you explore one of Italy’s best-preserved ancient cities, your archaeologist-guide brings every corner to life. Walk along original Roman roads, step inside beautifully preserved bathhouses with mosaic floors, and descend beneath them to see where slaves once tended the furnaces. Stand on the amphitheatre’s stage, wander through ancient taverns, bakeries, grain stores, brothels, workshops and apartment blocks, and discover hidden Mithraic temples and religious spaces—each explained with the clarity and passion only a specialist can offer.

Many travellers find Ostia Antica more rewarding than Pompeii. It is far easier to reach—just a 25-minute train ride from Rome—and offers a more complete picture of a genuine working-class Roman town rather than a resort city. With fewer crowds and a more peaceful, “undiscovered” feel, the site is not only more enjoyable to explore but also a more sustainable option with a lower carbon footprint.

Your experience begins in Rome at Piramide Metro B station, where you’ll meet your private guide and travel together to the coast. During the short journey, they’ll share the background of the region, the rise of Ostia, and its crucial role as Rome’s bustling port. Once inside the archaeological park, you’ll spend around 2.5 hours delving into the ruins at a comfortable pace, with plenty of time to ask questions and explore the areas that interest you most.

At the end of your tour, you’ll find yourself mere minutes from the beach — perfect for a relaxing stroll, a dip in the sea, or a fresh seafood lunch to round off your day.

Channel your inner-Maximus as you step out onto the Colosseum arena floor, enjoying exclusive access to this newly reopened section of the world's most famous amphitheatre. Don’t settle for half measures during your time in Rome. Seize the moment—carpe diem—and treat yourself to an immersive Colosseum arena tour with a private expert guide!

Unlike most other tours, this private tour gets you straight inside the Colosseum with timed-entry and out onto the arena floor through the Gladiator’s Gate. This is the route Rome’s gladiators took almost 2,000 years ago. Imagine the scene of them being greeted by the cheers and jeers of 50,000 spectators.

Your expert private guide will transport you back in time to the height of the Roman Empire when Nero’s Golden Palace fell and the Colosseum was constructed in its place. These were times when Rome was ruled by all-powerful emperors (sometimes wise, sometimes wacky), the city was flooded with exotic riches from around the world, and the Colosseum acted as the city’s main stage for showing off the animals and people that Rome had conquered and captured.

Next, we’ll climb the Palatine Hill, where Romulus founded the city. The Palatine Hill is a real archaeological wonder, home to settlements from the Iron Age to the 16th century. Gaze upon such sites as the Hut of Romulus, the houses of Augustus and Livia, and the Imperial Palace, where the emperors in their family engaged in ruling, politicking, and scheming.

The final destination on your Private Colosseum Arena Tour is the Roman Forum. As the beating heart of ancient Rome, the Roman Forum was once a bustling hub of markets, law courts, temples, and more. It was here that Julius Caesar was cremated, here where two disgraced emperors were murdered in 69 AD, and here where Cicero delivered the speeches that shaped western culture for centuries.

At the end of your private tour, feel free to stay and explore the Forum at your own pace.

There’s a saying between foodies: to truly understand people and places, you need to take a good look inside their kitchens!

Our Private Rome Food Tour does exactly that. We take the stress out of planning so you can relax and dine with peace of mind. With priority service and pre-reserved tables, our multi-award-winning food tour grants you insider access to the most authentic, locally-beloved restaurants, bars, flavours and recipes in the trendy neighbourhood of Trastevere.

Your private guide will lead you and your group through an area renowned for its buzzing nightlife and fantastic eateries. It’s here where you’ll discover the local hotspots that many tourists miss. Not only will you experience the mouthwatering flavours of Rome, but you’ll also discover the process, meet the makers, and truly understand why Roman Cuisine is considered one of the best in the world.

You’ll enjoy at least 10 different Roman dishes and some of the finest local wines and beer or non-alcoholic options. From artisanal meats and cheeses and creamy gelato to Roman-style pasta and pizza, you’ll treat your taste buds to the flavours of the Eternal City.

This experience is more than just simply trying different local foods. It’s a delicious journey into the world of Roman food; discovering the delicacies, the diet, the dos and don’ts that make Italy’s culinary culture so globally renowned. And with a private guide, we’ll cater to the needs of your group and personalise our stories to hone in on the information you care about most. What are you waiting for? Book a Private Rome Food Tour and get ready for the experience of a lifetime.

Please note that the places we visit and the food we try depend on the season.

This is a sustainable tour, meaning part of the profit goes towards reforestation

Summer’s coming! We ask our guests to bring a reusable water bottle to refill along our route to stay hydrated and also help us reduce waste.